[ad_1]

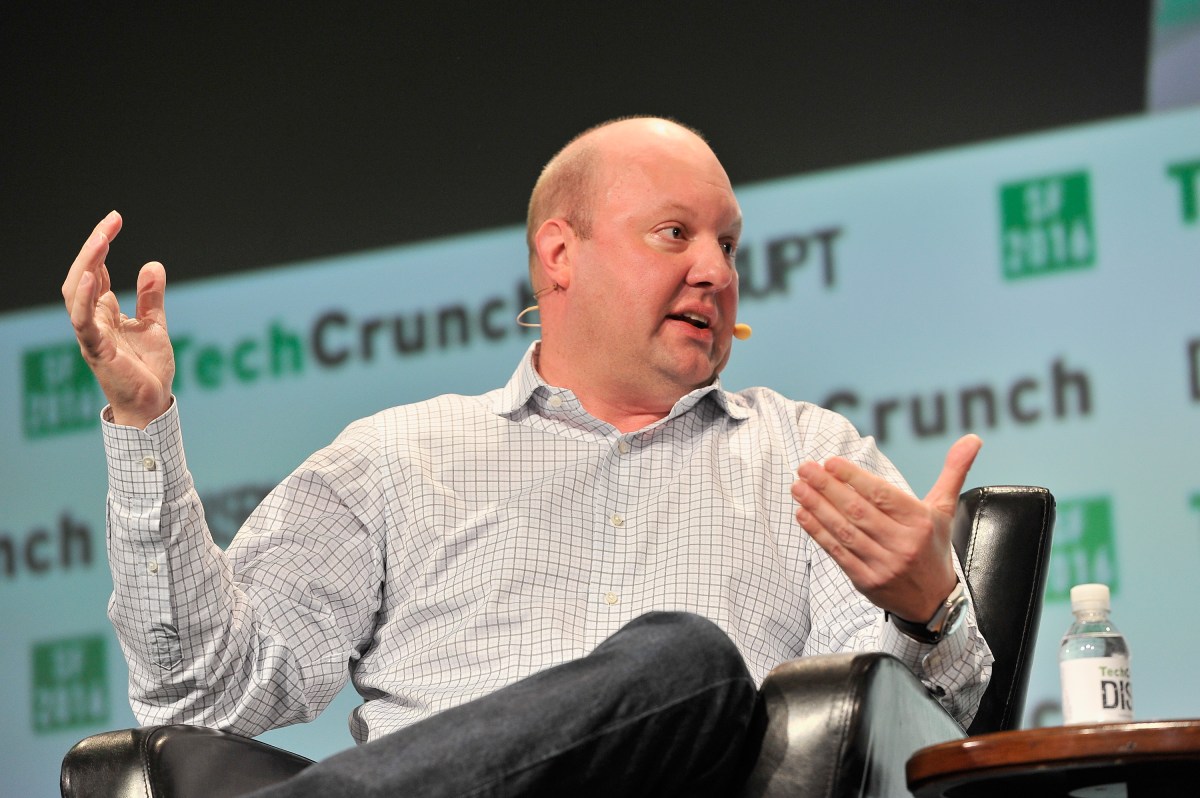

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen posted a manifesto on the a16z website, calling for “techno-optimism” in a frenetic 5,000-word blog post that somehow managed to re-invent Reaganomics, propose the colonization of outer space, and Manages to answer a question absurdly. The phrase “QED.”

Andreessen’s vision of techno-optimism may seem inspiring: He envisions a libertarian-esque world where technology solves all our problems, poverty and climate change are eliminated, and an honest meritocracy reigns supreme. Although Andreessen may call us “communists and Luddites” for saying so, his dreams are unrealistic, and based on a flawed premise that technology exclusively makes the world better.

First, we need to remember the biases that Andreessen brings to the table, primarily that he’s absurdly rich (worth an estimated $1.35 billion as of September 2022) and his absurd wealth comes largely from his namesake tech venture fund. Is related to investment. So, he’s naturally going to emphasize his techno-optimistic vision, because the success of tech companies means he’ll get even richer. When you have a financial stake in something, you become biased: This is why, as journalists, we can’t buy Netflix stock, then turn around and write an article about why Netflix is going to have a great Q4. Is.

But money can blind. At the beginning of his essay, Andreessen writes, “We believe that there is no physical problem – whether created by nature or by technology – that cannot be solved with more technology.” A16z is increasingly investing in defense companies, including Palmer Luckey’s controversial startup Anduril, which makes autonomous weapons. Is war the problem these companies are solving? What does “solution” even mean in the context of conflicts like the ongoing war in Israel and Gaza – isn’t true resolution an end to the conflict?

Another inconsistency lies in Andreessen’s claim that “technological innovation in a market system is inherently altruistic by a ratio of 50:1.” He references economist William Nordhaus’s claim that people who create technology retain only 2% of its economic value, so the remaining 98% “flows into society.”

“Who gets more value from new technology, a company that creates it, or the millions or billions of people who use it to improve their lives?” Andreessen asks.

We won’t lie and say that tech startups haven’t made our lives easier. If we’re out very late and the Metro isn’t running, we can take Uber or Lyft. If we want to buy a book and have it delivered to our doorstep by the end of the day, we can order it on Amazon. But denying the negative impacts of these companies is like blindly moving forward around the world.

Furthermore, it is implicit – but not stated in Andreessen’s argument – that these platforms have effectively turned large swathes of society into renters and the platforms into landlords. Perhaps they need a refresher on the evils of the “renter economy” and how counterproductive it is to innovators and entrepreneurship?

When was the last time Marc Andreessen walked the streets of San Francisco, where wealthy tech workers pretend not to notice the encampment of homeless people outside their companies’ headquarters?

When was the last time Marc Andreessen talked to a poor person — or an Instacart shopper struggling to make ends meet?

Andreessen’s argument is a contemporary iteration of trickle-down economics, the infamous Reagan-era idea that as the rich get richer, some of that wealth will “trickle down” to the poor. But this theory has been repeatedly rejected. Again: Do Amazon warehouse workers really get their fair share?

At one point, Andreessen makes the case that free markets “prevent monopolies” because “the market is inherently disciplined.” As any third-party Amazon seller will tell you – or anyone who has tried to get Eras Tour tickets – this is a point that’s easily refuted. Andreessen may argue that the US market is not truly “free” in the sense that it is regulated by agencies and lawmakers who empower those agencies to enforce policy. But the US has had its fair share of expanding illegal tech oversights, and each has spawned tech giants strongly inclined to crush – not suppress – competition.

Andreessen’s motivations become more clear when he lists those he considers his enemies.

In that section, he lists what he feels has subjected society to “mass demoralization.” This list refers to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 17 objectives that were created to inspire nations to strive toward peace. According to Andreessen, these are the so-called enemies “against technology and life”: environmental sustainability, reduction of gender inequalities, eradication of poverty or hunger, and more good jobs.

How do these 17 goals go against technology and life, when technology is already being used to achieve more life – already to create clean water, reduce mass production, and generate clean energy is being used. He has a vague, hollow way of writing that leaves more questions than answers; This leads to the idea that he probably never read the 17 Sustainable Goals, and is instead using it as a code word for something else. Then, Andreessen denounced ESG stakeholder capitalism, tech ethics, trust and security, and risk management as the enemies of his cause.

What are you really trying to say, Mark? That regulation and accountability are bad? Should we pursue the development of technology at the expense of everything else, in the hopes that the world will be better off if Amazon’s stock breaks $200 a share?

Andreessen normally has a coded way of speaking, so it’s no surprise he’s so angry at the UN’s goals of supporting those most at risk. He talks about the planet being “dramatically underpopulated” and specifically points out that the way in which “developed societies” are depopulating seems to support one of the core tenets of prosocialism. It happens. He wants 50 billion people to live on Earth (and then some of us colonize outer space), and says “markets” can generate the money needed to finance social welfare programs. (Let us repeat the question: Has this guy recently been to San Francisco?) He also mentioned that Universal Basic Income would “turn people into zoo animals to be farmed by the state.” (Sam Altman would undoubtedly disagree.) He wants us to work, to be productive, to be “proud.”

The missing link here is how we can use technology to actually care for people; How to feed them, how to clothe them, how to make sure the planet doesn’t reach temperatures so high that we all melt. What’s missing here is that San Francisco is already the tech center of the world and one of the most unequal places in the universe socially and economically. What’s missing here is that the technological revolution has made it easier to hail an Uber or order food delivery, but how those drivers and delivery people are being exploited, and some are struggling to maintain decent wages. Didn’t do anything about how to live in their cars.

There are lines and lines to analyze in his manifesto, but it all goes back to the point that what is missing here is life: the element of living life and all its nuances. He really takes a ‘you’re for technology’ or ‘you’re against it’ approach to using productivity to help make lives better. He talks about the economic structures around which life revolves, without mentioning the complex ways they actually affect people.

Many tech giants talk about creating a world over which they have no control. We see Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg “move fast and break things” and then testify before Congress about election interference. We see OpenAI founder Sam Altman draw parallels between himself and Robert Oppenheimer, and not hesitate to think too hard about whether pushing the boundaries of technological innovation at any cost is a good thing.

Andreessen is the product – and an engineer – of a tech bubble that doesn’t understand the people it seeks to serve.